THE LIFE AND WORK OF WILLIAM TYNDALE PART 2

By Michael Hobbis,

CW Committee Member

Part 2 (of 3)

When we began to look at the life of Tyndale in Part 1, it was remarked that in terms of the recognition of his undoubted graces and abilities he was – and still is – surprisingly unacknowledged as the one man who possibly played the most

important part in the spiritual life and heritage of the English speaking peoples.

It has been suggested that this repression, even denial, of the importance of his contribution to this nation – and others – was due to his attachment to Martin Luther. Like Luther, Tyndale impresses the reader of his written works with his obvious disregard for the praise and plaudits of men and he fearlessly declared the whole counsel of God to Kings, prelates and the common man alike. He did not

bow to the traditions of the professing Church; but emphasised that Christianity is the freedom and liberty of the individual from the traditions and lordship of prescribed religion in his access to his Redeemer and Creator.

True Christianity has always been perceived as a threat to the political and religious powers – the rulers and Kings of the earth. In his works The Practise of Prelates and The Obedience of the Christian Man, he put Christ and His laws before a desire for fame and honour. In short, like Luther, he would not toe the party line. As with John the Baptist who, 2000 years before, reproved Herod, Tyndale reproved King Henry VIII for his divorces and adulteries and exposed the corruptions of the professing Church.

Whether or not this is a correct assessment of the reasons for the world overlooking Tyndale’s true service for his Lord and Master – two obvious facts are before us. Firstly, that many people today are ignorant of the part he played in the revival and reformation of true faith in England. Moreover, for those who choose to search Google today for the description of Tyndale’s translation work, very often it will be erroneously suggested that the work of translating the New Testament from Greek to English was due in large measure to one George Roye, an associate; a man who – far from being an indispensable help – proved to be something of a burden and hindrance. Not only did Roye plagiarise and corrupt Tyndale’s work, but he did not even understand Greek. He took upon himself, without asking Tyndale, a revision of the translated New Testament and in doing so made many mistakes.

A second undeniable fact is that in the work of translating the King James Bible of 1611, those translators used about ninety per cent of Tyndale’s New Testament. They were undoubtedly Godly and learned men and performed a valuable work. Yet in the long preface of the translators to the reader in all their acknowledgements of their helps and sources, from works such as the Septuagint and other translations, the name of Tyndale is never mentioned; even though they were indebted to him for the major proportion of their work in translation.

These men were in the main Churchmen, seeming to slight the man who under God gave us the words Jehovah; Passover; scapegoat; shewbread; peacemaker; mercy seat and many other now familiar words in our AV Bible. We owe to William Tyndale phrases now firmly fixed in common parlance – e.g.salt of the earth; powers that be; the patience of Job; the scales fell from their eyes – and hundreds more.

What perhaps is even less well known is that we also, by the grace of God, owe to Tyndale much of our English prose style. His gifts of language were such that he brought rhythm, cadence,

suppleness and lucidity into English prose. This has been noted by David Daniell who said of this man – “Such flexibility, directness, nobility and rhythmic beauty showed what language could do.”

This man not only coined new words but gave us a prose style used by Shakespeare and many other succeeding literary ‘greats’; whereas old English, because of strong Latinate influences, was harsh and scholastic. Now Tyndale, in his translation of Greek and Hebrew, brought into English a freshness introducing the influences of the Greek and the Hebrew, the very languages which God chose as the vehicles to convey His infallible inspired truth. He translated the Old Testament into English as far as Chronicles and in doing so stated that he could virtually place word for word in translating the Hebrew since the similarity was so great between these two languages. In Tyndale’s day 6,000,000 people spoke English – now it is about 600,000,000; all these owe to Tyndale those beneficial blessings from his translating work.

One of the saddest effects of the modern Bible versions today is in their seeking to be relevant to the post-modern man. This new mode of thinking, with its contemporary relativism and all that goes with it, jettisons the clarity and softness of Tyndale’s ‘Biblical’ English, replacing it with the harsh grating coarseness of a modern speech, which seeks to run from all ideas of godliness as fast as it can. We only have to consider some modern day expressions to realise that language really does reflect the spiritual state of a nation and men’s souls.

I make no apology for having taken up so much space out of this account of the life of this brother in Christ in order to emphasise the massive debt that we all in this land owe by God’s grace to the life and work of one man; viz, William Tyndale. Some men’s works go before them; other’s follow after.

We last left Tyndale still in England, but having the increasing burden to give the Scriptures to every Englishman, in a translation as faithful and accurate as possible.

He had been advised to approach Bishop Tunstall in London in order to get him to sponsor Tyndale in his translation work. Tunstall had been a friend of Erasmus, so he had reason to hope for a good reception. Taking with him an example of his own Greek translation, he approached this influential Prelate. But Tunstall, probably fearing that the Bible translated might open the gates to he knew not what, rebuffed him with excuses. He was also a politically astute churchman and could foresee dangers from this zealous evangelical. It was while in London that William Tyndale met John Frith and both men were ever after good friends. In truth it was believed that Frith was born into the true faith through the influence of Tyndale – in future days he referred to him as “my son in the faith”. After some preaching in various London churches, he became aware of the dangers on every hand for those who proclaimed the pure truth of the Gospel. Seeing many whose eyes God had opened taking their journey to Europe, he took what books and papers he could and with financial help from Humphrey Monmouth, a merchant, he went to Hamburg, Germany in 1524, never to return to England again.

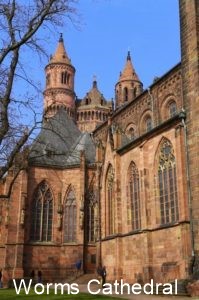

Because of the need to keep his whereabouts secret, the actual details of his European journeys are vague. At some stage he met with a wandering English friar, William Joye, who had been affected by the preaching of the Gospel. He performed the function of an assistant in Tyndale’s attempts to arrange the printing of his new translation. (This man should not be confused with the previously mentioned George Roye whom Tyndale met at a later stage in his European journeying.) Unfortunately, Joye proved an embarrassment, as he had a penchant for writing rhymes against the Pope, the King, Wolsey and others; this was trouble Tyndale did not need and he eventually parted from him. Meanwhile, they travelled from Hamburg to Wittenburg, where he probably met Luther – and then to Cologne. While there, the translation and printing of the New Testament began. However, one John Cochloeus, who considered himself chosen by God to strongly oppose Luther and the Reformation, set his sights on Tyndale and betrayed him to the authorities. Tyndale and Joye gathered together what printed sheets they could and took flight down the Rhine to Worms. Due to the sphere of Luther’s influence, they were much safer there. We learn all this from the commentary of the enemy, Jon Cochloeus, in his work Acts and Writings of Luther, wherein he writes of this encounter with Tyndale.

In Worms, printers such as Peter Schoeffer were quite willing to print for Tyndale. Whereas previously Tyndale had planned to print 3,000 New Testaments, now he intended 6,000. These were taken by German merchants into England and distributed with the aid of one Thomas Garret, who was later martyred. Henry and Cardinal Wolsey were only too aware of these translations coming in, but mostly were outwitted by the merchants who were also bringing in Luther’s works. Tyndale and Joye were at Worms for some two years and Joye, eventually becoming too troublesome, they parted, with Joye going to Strasburg. The first New Testaments came to England in 1526, towards the end of February. As has been mentioned, it is a matter of some uncertainty as to the exact movements of Tyndale, as his aim was to remain in relative obscurity to avoid any dangers. However, it is recorded on every hand that he met with Luther and seems to have been greatly impressed by him.

About this time, with the planning of a merchant friend of Tyndale, Tunstall began buying the Bibles from the merchants and then burning them. This providentially worked in Tyndale’s favour as now he had the money to print more – and gave himself to further revision and translation. Tunstall expended vast sums of money for a time before he became aware that his money was being used to further and perfect this work of translation. Of all the thousands of copies which found their way into England, the very few which remain today are in museums and libraries.

Tyndale not only worked at translation, but while moving from place to place wrote The Practise of Prelates, which was a scathing rebuke of the abuses in the Churches. He also wrote The Obedience of the Christian Man. These works found their way into the hands of the common man and the King of England and a New Testament also was placed in the hands of another almost equally famous personage, which we shall discuss in the third and final part of the life of this valiant champion of Christ and His Truth.

_______________________________

“As the stars do not make heaven, but only decorate and adorn it, even so works do not merit Heaven, but adorn and decorate the faith which justifieth.” Luther